Leonard Peltier, the Indigenous rights activist held for almost five decades in maximum security for crimes he has always denied, has made a plea for clemency so that he can wander freely and hug his grandchildren for the first time.

In an exclusive interview with the Guardian to mark the start of his 48th year in prison, Peltier spoke about the pain of being deprived of his liberty, and his yearning to be reunited with his homeland and community after so many years.

“Being free to me means being able to breathe freely away from the many dangers I live under in maximum custody prison. Being free would mean I could walk over a mile straight. It would mean being able to hug my grandchildren and great-grandchildren,” said Peltier, aged 78.

“I have been kept away from my family and only seen them a few times over the past 47 years. It is more than hard, especially when the kids write to me and tell me they want to see me and I cannot afford the cost of travel. If I was free I would build me a home on my tribal land, help build the economy of our nations and give a home to our homeless children,” Peltier said in an interview conducted over email via one of his approved contacts.

Peltier, an enrolled member of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa tribe and of Lakota and Dakota descent, was convicted of murdering two FBI agents during a shootout on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota in June 1975. Peltier was a leader of the American Indian Movement (Aim), an Indigenous civil rights movement founded in Minneapolis that was infiltrated and repressed by the FBI.

The 1977 murder trial – and subsequent parole hearings – were rife with irregularities and due process violations including evidence that the FBI had coerced witnesses, withheld and falsified evidence. Amnesty International, UN experts, Nelson Mandela, the Dalai Lama and the Rev Jesse Jackson are among those to have condemned his prolonged detention as arbitrary and politically motivated and called for his release.

Peltier, who is currently detained in Coleman, Florida, has spent 46 of the past 47 years in maximum security. Multiple recommendations to lower his prisoner classification, so that he can be transferred to a less restrictive prison closer to his family, have been rejected.

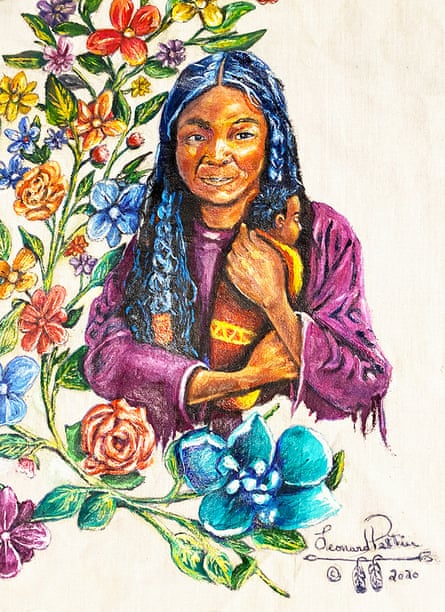

Life inside for Peltier has got even harder and more lonely since the start of the Covid pandemic, with frequent and unpredictable lockdowns, limited access to medical care and virtually no access to the phone, computers or the art room – where Peltier would spend much of his time painting and writing.

“This place is becoming a complete lockdown institution. I’m living in a 6x12 cell built for one person that I am forced to share, where we spend 24 hours a day during these frequent lockdowns. You’re on guard every moment of the day … I am not receiving the medical treatment that I need and I suffer a lot of pain from the illness that needs treatment. A lot of programs are being taken away, and other privileges which make it even more stressful,” said Peltier, whose health and mobility have significantly deteriorated since he contracted Covid last year.

In 2022, UN experts called for Peltier’s immediate release after concluding that his prolonged imprisonment amounted to arbitrary detention.

“Mr Peltier’s detention has been prolonged by parole officials who have departed from guidelines and failed to follow regulations pertaining to his parole proceedings. This, in addition to the influence of the FBI over the case, is the reason why he remains in detention during the Covid-19 pandemic, which is a threat to his life,” they said.

Last month, a former FBI agent close to the case accused the agency of harboring a vendetta against Peltier and called for his release. Peltier contacted the Guardian after Coleen Rowley’s unprecedented intervention calling for a presidential pardon.

Rowley, the former legal counsel at the Minneapolis FBI office, which played a key role in policing tribal nations, told the Guardian that in the 1990s she helped ghostwrite an op-ed arguing against Peltier’s release.

Peltier said: “I’m very disappointed that she was involved in creating false evidence and took this long for her to come forward. However, I am grateful now that she did decide to tell the truth … I am hopeful that Biden will sign my clemency. But I am not sure there will be any difference.

Peltier’s hopes have been raised and crushed by numerous US presidents, Democratic and Republican, including last-minute changes of heart by both Bill Clinton and Donald Trump, according to his attorneys. The status of his current clemency application is unclear.

On Monday, vigils calling for his release will be held by his supporters across the country including in Sacramento, California, which his granddaughter Julie Richards will attend.

“Grandpa Leonard is an inspiration to me and so many others. He deserves to see the light outside prison walls of day, so he can get back and stand with the people, we need him,” said Richards, an anti-pipeline and water activist on Pine Ridge reservation whose biological grandmother Geraldine High Wolf, a member of the AIM, who adopted Peltier as her brother.

Peltier has said that his political activism was driven by the racism and brutal poverty he experienced every day growing up on the Turtle Mountain Chippewa and Fort Totten Sioux reservations in North Dakota, and living through the federal government’s forced assimilation policies at boarding school.

Indigenous activism – and the political, cultural and legal landscape – have evolved since the AIM’s heyday, but the pandemic exposed and exacerbated the housing, health, economic, food and water inequalities still faced by Indigenous Americans, shining the spotlight on the federal government’s failure to abide by its treaty promises.

“Nothing has changed for me or my beliefs. I hear life is somewhat easier today with not so much hunger and open racism as when I was growing up, but we still have a ways to go until we are free from the concentration camps systems I grew up in. Although we have made many gains and won some victories in the courts, we are still fighting against the large corporations for the theft of our lands and minerals. Of course any and all victories are great but the cost is high – as at Standing Rock when many were imprisoned.”

Peltier has no option but to hope that this time the US government will grant him clemency despite the FBI’s 47-year effort to block his freedom.

“Of course I know from my own experiences that the justice system sucks in America, and for us natives has not changed much in that area. It’s 2023 but it’s still a very racist system,” he said.